When brand promises collide: Atlanta Falcons stadium and Chick-Fil-A

=======

Corrected due to major error. I mixed up the Braves baseball team stadium and the new stadium for the Atlanta Falcons football team. This error was pointed out in the comment by Alex B., below. While the text has changed to reflect the correction, the comment text remains.

=======

I have "always" had a problem with the concept of branding because I come out of the nonprofit world, where the focus is on "mission and identity."

But the reality is that branding is merely a tool used to present and market an organization in a very comprehensive way. Branding is about identity.

Sure, lots of nonprofit organizations don't use branding very well or look to the private sector to lead their efforts, e.g., Smithsonian's now cancelled initiative with Target, but some organizations including government agencies are leaders in using branding to shape the way they organize and deliver services to spark positive changes.

Some examples include the way that the Salt Lake City Libraries are branded as "City Library," the Idea Store libraries-adult education centers in the Tower Hamlets Borough in London, or how the Department of Transportation in Tempe Arizona is branded as "Tempe in Motion," or TIM.

In DC, the way that the DC Water and Sewer Authority has rebranded as DC Water and the DC Department of Transportation as d. are other examples, although I would argue in both instances, the brand is more about the logo rather than an extension into every element in how the agencies organize to deliver and market their services.

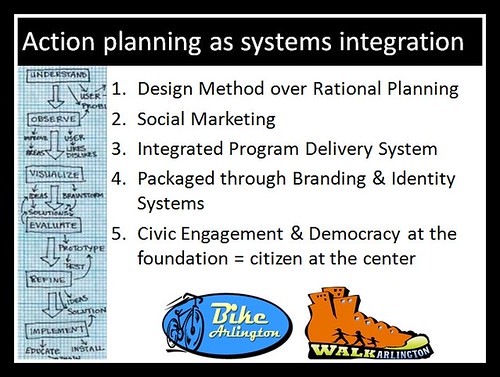

Government agencies have a lot of opportunity to do a better job through what I call "action planning," which is distinguished from more traditional planning processes by employing the design method, including branding and identity systems, and by integrating program delivery (implementation) into the system.

I have gotten into "arguments" about this on nonprofit boards that I have served on, in terms of ensuring that what we do is congruent with what is supposed to be the identity and "promise" of the organization.

Those arguments are based on my thinking that boards are the "brand managers" of an organization. I expressed this concept in the commercial district revitalization framework plans for Brunswick, Georgia and Cambridge, Maryland in 2008 and 2009, writing that:

... elected officials need to take their responsibilities as stewards and managers of a community's image very seriously:

Just as the study team believes that “we are all destination managers now,” elected and appointed officials in particular and in association with other community stakeholders serve as a community’s “brand managers”—whether or not they choose to think of their roles in this manner.

That means that decision-making on land use and zoning, business issues, infrastructure development (roads, sewers, water, utilities, transit), technology (broadband Internet, etc.) and quality of place factors (arts, culture, historic preservation and heritage, education, public schools and libraries, urban design, etc.) must be consistent and focused on making the right decisions, the decisions that collectively achieve and support the realization of the community’s desired vision and positioning.Something else I read termed this as making "brand deposits" or "brand withdrawals," how the decisions and actions concerning a brand either make positive contributions and build the brand or the actions are negative and diminish the value of the brand, its reputation, aspirational qualities, etc.

Atlanta. This comes up in an interesting way in Atlanta with the new Atlanta Falcons football stadium--the Mercedes Benz Stadium--and one of their food vendors, the Chick-Fil-A chicken fast food chain. Chick-Fil-A is owned by a religious family and ever since the company's founding in the 1940s they have chosen to be closed on Sundays.

Chick-Fil-A has chosen to keep that policy in force in the stadium, even in the face of the reality that most football games are played on Sundays ("Chick-fil-A addresses decision to close Sundays at Mercedes-Benz Stadium," Atlanta Journal-Constitution; "The Falcons' new stadium has a Chick-fil-A, which won't be open for most Falcon games," Chicago Tribune). That ought to have been a deal breaker in terms of the expectations of the Atlanta Falcons.

Besides making the point that the business being open during all events should have been an item in the contract between the managers of the stadiums and the "tenants" (similar to the point I make about cities, stadiums and arenas, and access to transportation being an element of the initial contract, not something to bring up later, especially when the government entity usually has little leverage and must rely on the "goodwill" of the counterparty), this is an illustration of the collision of two very different brand promises.

While I respect the choice of Chick-Fil-A to run their business the way they want and there is no question they have been very successful at doing so ("How Chick-fil-A went from cult favorite to fast food behemoth," Eater; "Chick-fil-A Shifts Brand Strategy from Kows to Customer Experiences," Top Right Partners), the Atlanta Falcons should have represented equally their brand promise which means that all food vendors are operational when the stadiums are open, and not entered into a contract with Chick-Fil-A.

Is an opportunity being created for another firm to step in? But it could be that this is what we might call a "Reese's Pieces" movement.

In the movie "E.T." the scriptwriters wrote a scene where E.T. is lured by the children placing a trail of "M&M" candies. But Mars Corporation didn't want to participate.

Hershey Chocolate stepped in the breach, and the publicity garnered from this product placement made Reese's Pieces--a line extension of the already successful peanut butter cups--equally successful. M&M's decision ended up creating a viable competitor when one hadn't existed previously ("Did You Know Spielberg Originally Wanted M&Ms for E.T.?," Moviefone).

Why not "force" stadiums to boost local independent businesses rather than chains? This is a tricky issue because communities funding stadiums and arenas have different objectives than either professional teams or the leagues, which in turn can have different sponsorship arrangements that clash with support of local business. (Although recently, the Chicago White Sox developed a tiered sponsorship arrangement, carving out a separate "local craft beer sponsor," from national beer sponsorship relationships in association with a change in agreements. See "White Sox split with Miller, ink beer deal with Modelo Especial," Crain's Chicago Business.)

And the reality is that many sports stadiums and arenas, like the Washington Nationals baseball team, are doing a lot in this realm, even if it tends to be more typical that these become licensing arrangements with a master food service contractor.

Food is now recognized as a major element of the game day experience ("Enhancing the Fan Experience in an Ever Changing Industry," Faithful Gould). A report ("Sports and Entertainment Venues: What do Fans Really Want") based on the ongoing Fan Experience Study by Oracle Hospitality ranks food and beverage as the foremost element of attending an sports event.

While Popeye's is associated with New Orleans and KFC with Kentucky, there are great independent fried chicken purveyors in Greater Atlanta that could leverage a "we are open when the stadium is open" marketing approach to build their business -- outside of the stadium and within it, were the team to choose another vendor.

The Eater article "Where to eat fried chicken in Atlanta" lists sixteen exemplary choices.

Sure Chick-Fil-A is considered an iconic Southern food business and is even based in Georgia, but the reality is their fried chicken isn't any better than KFC or Popeyes.

... although it is interesting to see a professional sports team be on the losing end of this kind of battle, rather than local governments, which are more typically the entity that gets the short end of the stick in such negotiations.

Labels: branding-identity, retail planning, sports and economic development, stadiums/arenas

2 Comments:

Major correction:

Mercedes-Benz Stadium is not a baseball stadium. It will not serve the Braves. It will be primarily for the NFL's Falcons, and also Atlanta's new MLS team.

The Braves have nothing to do with this. They've got their own new stadium in Atlanta's suburbs (that's causing all sorts of problems anyway) which also includes Chick-Fil-A among their concession stands: https://atlanta.eater.com/2017/4/5/15094224/suntrust-park-food-atlanta-braves-stadium

The fact that they included a Chik-fil-A in a stadium built for a league that plays mostly on Sundays is really amazing.

However, I don't see the case for brand expectations. The Falcons have complete control over the stadium experience, including concession leasing. They have no one to blame but themselves.

More interesting to me is the approach they've taken by dramatically increasing the number of concessions in the stadium while aiming to offer street pricing:

http://www.atlantamagazine.com/news-culture-articles/will-the-falcons-plan-to-lure-fans-with-cheap-concessions-work/

We'll see how long that lasts.

Grr. Will have to correct.

Post a Comment

<< Home