Civil rights, public accommodations laws, and religious belief exceptions

When I was more heavily involved in historic preservation matters, I led a campaign to landmark an "old" arena/coliseum building in the H Street neighborhood of Washington, DC (now the building is about to become a high profile REI outdoor store, "We're Opening a New Flagship in Historic Uline Arena in Washington, DC").

One of the things I learned while doing the research to justify landmarking was the place of the building in the timeline of civil rights history specific to local Washington, DC. Technically, the city did not legalize segregation but in the late 1800s, laws banning segregation were hidden, and public accommodations--but not the city's transit system--but most everything else, stores, restaurants, hotels, housing, and hiring became segregated.

Later, while supposed to be segregated, the practice at baseball games at Griffith Stadium was integration.

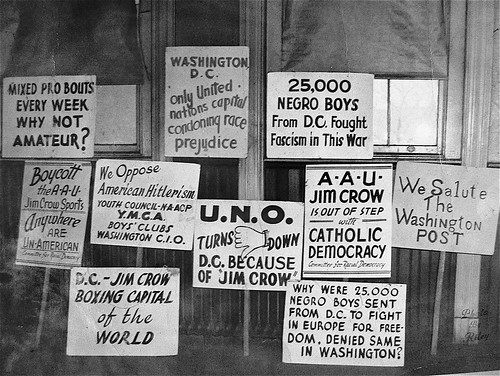

After World War II, E.B. Henderson, a professor, director of sports for DC Schools, and a leading activist within the NAACP, led a campaign where people protested every event held at the Uline Arena, in order to get the owner--who claimed that integration of events was at the discretion of the sub-tenants renting use of the building--to make integrated events that standard practice. In 1949, the owner capitulated. (This was reported in the black press at the time.)

Protest Signs, Campaign to integrate Uline Arena, (1948-49).

I believe this influenced the holding in the Thompson Restaurant case four years later, where segregation in public accommodations in the city was prohibited, and this case in turn had to have influenced the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, which included a DC case, Bolling v. Sharpe.

The fight did not end with integrated schools, much more advocacy and legal action was required over the next 15 years to affirm civil rights protections in DC and US laws, as we know.

And as Black Lives Matters and related movements demonstrate now, it takes many decades to counter the legacy of hundreds of years of structural racism and economic segregation.

Public accommodations and personal practices. This comes up with regard to various laws concerning discrimination concerning sexual orientation or other matters, such as filling a prescription for birth control.

I don't see how it can be legal to provide a "religious exception' to what need to be considered civil rights public accommodations and equal protection laws. (Obviously, I don't agree with the "Scalia" Court holding in the Hobby Lobby case with regard to health insurance and coverage for abortion. The company's policy was upheld because of the beliefs of the leaders of the corporation.)

If you're a licensed pharmacist, I think it's fine to choose to not fill a prescription, provided your license to be a pharmacist is revoked, because you shouldn't have a choice whether or not to fill a legally prescribed prescription. In short, as a matter of business and licensure, pharmacists have a duty to fulfill all of their responsibilities.

Similarly, as an elected official, Kim Davis, the county clerk in Kentucky who refused to grant marriage licenses for gay couples, should be removed from office as being unfit to perform the duties of the position ("Kim Davis stands ground, but same-sex couple get marriage license," CNN). The same for the Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court ("Alabama chief justice orders halt to same-sex marriage licenses." Reuters). The law is the law.

If you're licensed/incorporated as a business selling to the public, you should have no right to pick and choose your customers on the basis of race, creed, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, etc. (although I am fine with "firing customers" in certain situations, see "When, Why, and How to Fire That Customer," Bloomberg, but for strict business reasons only).

Arlene's Flowers in Richland, Wash., refused to provide flowers for a same-sex wedding. Above, the store in 2013. (Bob Brawdy / Tri-City Herald)

Christian Science Monitor has a story, "A florist caught between faith and discrimination," about a florist in Washington State who refused to provide flowers for a gay wedding ceremony, even though the request came from a long time customer. She is now facing a lawsuit brought by the ACLU which she is likely to lose. (Also see "Florist who rejected same-sex wedding job broke Washington law, judge rules," LA Times.)

Choosing to serve someone or not because of their race is illegal. Equal protection should be afforded to people generally, including on the basis of sexual preference, use of contraceptives, etc.

I have no empathy or sympathy for the position of the owner of Arlene's Flowers, Baronelle Stutzman. As a retail business, she should serve all her customers, not pick and choose. Otherwise she shouldn't be in the business of serving the public.

Labels: civil rights, civil society, equity, law and the legal process, religion, retail business promotion

6 Comments:

interesting.

https://medium.com/@nntaled/the-most-intolerant-wins-the-dictatorship-of-the-small-minority-3f1f83ce4e15#.256d4qoul

Very long shaggy dog story.

In law school I tried to write a paper on corporate law, and how it evolved out of agency into something else.

(the something else is the ultimate market theory of the corporation)

Tremendous failure, because I am not smart enough to write such a paper.

The professor at the time tried to console me by saying the problem is we don't have the language to talk about that anymore -- the market view has become so accepted.

Or as we say now, neoliberal.

I had hopes for Obama since he taught law in the belly of the market beast (Chicago Law) that he had learned how to do that and create a new language.

IN that, and in many things, he has not.

It isn't a new language, it is an old one.

The neoliberal view is "We've all got rights" and the market philosophy.

(Goes a lot back to VOICE and EXIT as well)

In a right-oriented viewpoint, we should be be forced to do those things.

Just like Uber should be allowed to do whatever they do.

The French view of the state is older and and stronger.

In France, your logic prevails and you can't claims rights.

You also can't wear a hijab and do other things. You might even be forced to weak a bikini at the beach.

Likewise, in places in the US where the state remains strong -- say airport security -- you don't get to make those claims.

Like your infrastructure arguments, these are very old arguments in new bottles on the rights on minorities to hijack a larger entity.

(Not much different than say car users in the 1920 demanding special rights on roads vs other users)

The sun may have cooked my brains. Whenever I read Taleb and agree it is never a good sign.

well I am more out of my depth than you. Anyway, wrt "market theory of the corporation" I guess you could argue that when the SC ruled that the corporation is a person, even though corporations compared to an average person, can be comparatively-relatively immortal, corporations were able to assert rights/market theory wise, etc.

E.g., the right to say anything (commercial speech), First Amendment, rather than being held responsible for being truthful. (E.g., the current Exxon controversy over climate change lobbying vs. the science.)

I don't know enough about the difference between English and French legal systems. When I thought about law school, I thought it'd be interesting to go to Tulane, in order to learn.

Well, it does go back to that debate.

Corporations originally couldn't be sued. They were collections of agents -- so it was an improvement that a corporation cold be a person and therefore sued. Or since it was a special grant you have to get the state to approve a lawsuit. A version of sovereign immuniity.

Didn't know that. (Hmm, I wonder if it was covered in those business law classes I took. Probably but I don't remember at all.)

Transformation of American Law, Horowitz.

He goes off the deep end in the last 50 years but I'd ague it was the same neoliberal pressure that broke everyone else.

(Take planning, which the smart kids think is evil now, but was a radical innovation in the 1920s.)

Hell, I could even tie that back into Lionel Trilling. But again too smart for me.

But smaller takeaway. Corporation=people was meant to control them, not to enable them. Then again anti trust was meant to keep corporations small, not to enable them to grow.

... the laws of unintended consequences.

When you have phalanxes of lawyers (and accountants) working for you, to maximize your advantage, it shouldn't be a surprise that advantages were reaped, rather than more careful control.

======

planning, law, it's the same. There is a story in the book _Strategic Marketing for Not for Profit Organizations_ by a social work professor at UM. He recounted teaching a class on planning and budgeting at Berkeley, talking about PPBS and other methods developed during WW2 at Ford Motor, used by McNamara wrt Vietnam, etc., and the students objected to the use of the "criminal methods."

He went to his car, got some nails, a vase, a hammer, and a piece of wood. He pounded some nails into the wood, and then smashed the vase.

He made the point that tools are tools, it's how you use them.

Frequently I have to admonish myself because I realize that I am not always asking the right question. Planning can be good or bad. A technique may not "work in the suburbs" generally, but what are the requirements to make it work should be the question that is asked. If you ask and answer, maybe it still won't work, or maybe you get more insight into the dynamics of what works where and why.

(This is relevant to a piece I'm working on about the new Cafritz development written up in the Post a few weeks ago, where they are mixing residential and office uses. I got a walk through a few days ago, and I realized that in some cases, like the point of Dan Reed's suburban innovation entry in GGW a couple weeks ago, these things will work, even if in most they won't.)

Post a Comment

<< Home